October 17, 2025

Studying Mason and Personalism with Jennifer Spencer, EdD

Scholar in Residence Program, 2025

Beginnings

In November of 2021, I was sitting in Dr. Deani Van Pelt’s home office in Canada when she handed me a book she was reading. “Have you read this?” she asked. It was a copy of An Introduction to Personalism by Juan Manuel Burgos. “No,” I answered, “I’ve never heard of it.” As she talked about the book, she reached towards the shelf again and pulled down What Is a Person? by Christian Smith. Though she had not gotten very far in either of them yet, she sensed, as I did, that they might contain insights relevant to Charlotte Mason’s philosophy. After all, Mason’s central thought was that the child is born a person. Any book that expounded on what that means was bound to be interesting, at the very least. I added both to my Amazon cart (as one does), and we continued our visit. This turned out to be one of those rare moments in life where you bump into an idea and, though the impact doesn’t feel strong at the time, it nudges you just enough to alter your life’s trajectory. Nearly four years later, I would find myself digging through archives in Cardiff, Ambleside, and Kendal, looking for evidence of a direct tie between Mason and personalism.

By the time I returned home from my 2021 trip to Canada, my new books had arrived. I flipped through them and skimmed a few sections that caught my eye. There was so much gold there, but they were so dense that I just couldn’t devote the time or mental energy that would be required to fully understand them. These were books for another day, so on the shelf they went, and I got on with my duties leading the Alveary.

I left that position just a few months later. In December, Deani and I were talking again, this time by phone. She was working on editing the monograph series, and the deadline was quickly approaching. She wanted to write one on Mason and personalism, but there just wasn’t time. “Oh, Deani, that one is too important! There has to be a monograph on personalism!” I said. We decided we would join forces to get it done. Deani would articulate what she had gleaned about personalism, and I would focus on how those ideas related to Charlotte Mason. Our monograph, titled Students as Persons, was published the following summer.

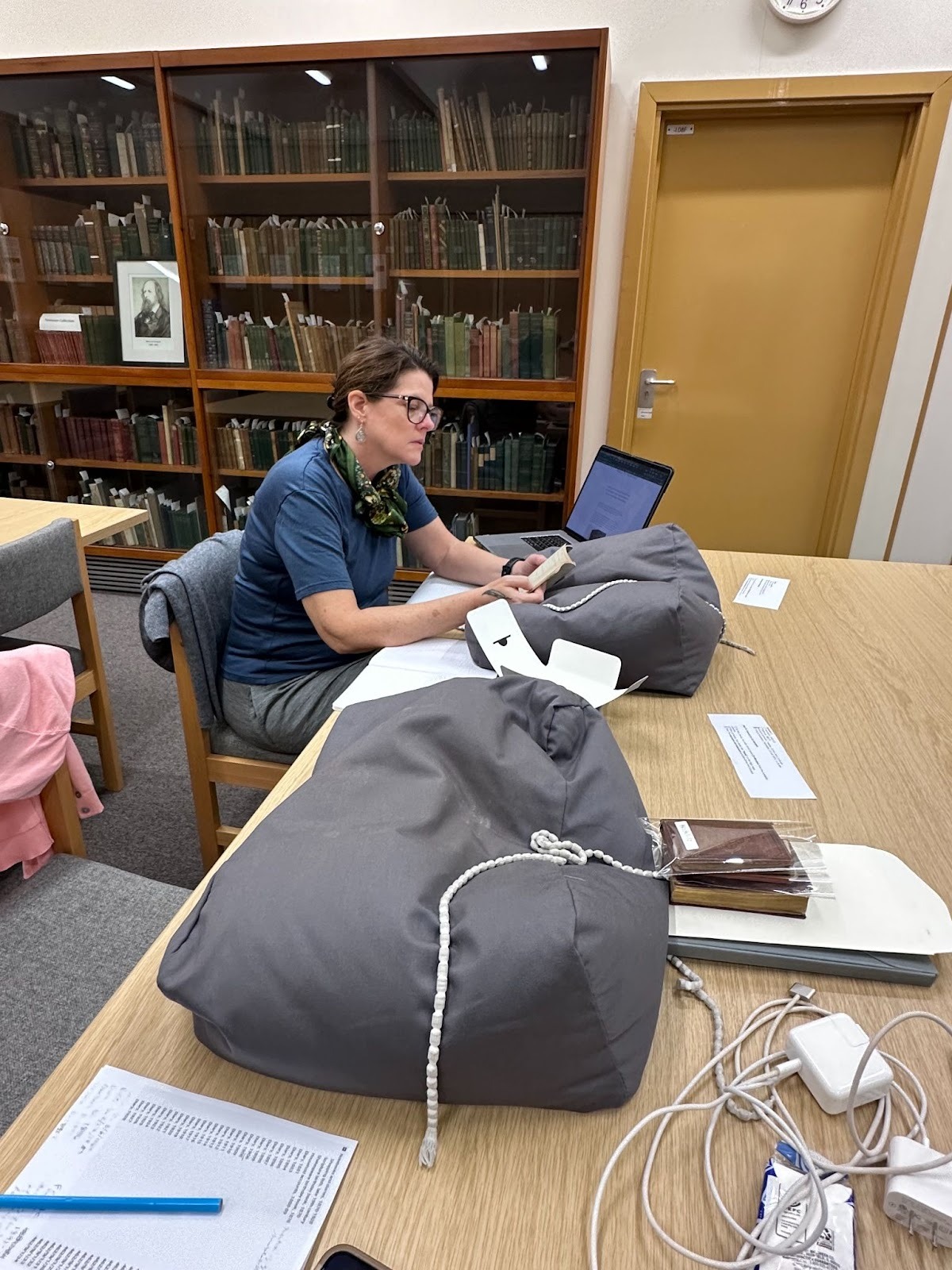

Working on that project renewed my curiosity. No, “curiosity” is not the right word. “Obsession” might be closer. I needed to understand personalism and figure out why it had so much in common with Charlotte Mason. When I returned from the Centenary Conference in Ambleside in 2023, I called Lisa Cadora and asked her if she wanted to read Christian Smith’s book with me and hash it out together. When we finished that one, we read Burgos. We found ourselves making charts, cross-referencing names, following rabbit trails, and being so incredibly nourished by it all. Ultimately, our book study morphed into a formal research project that would send the two of us back to the UK this past summer as Scholars-in-Residence for The University of Cumbria and the Charlotte Mason Institute.

Centrality of the Person

In our two years of exploration, we have encountered a number of iterations of personalist thought. The common thread that runs through them all is the centrality of the person. Essentially, personalism says that any action, organization, theory, economic system, religion, or government is good inasmuch as it honors the inborn dignity of every person and is bad inasmuch as it does not. Personalism is most closely associated with Europe from the 1930s onward. In fact, Burgos argues that personalism belongs exclusively to thought that originated in this specific time and place. Its most widely-known thinker is undoubtedly Karol Wojtyla (Pope John Paul II), whose contributions prior to his ascendancy brought this fairly niche school of thought into the international spotlight. Wojtyla’s ideas continue to be taught in Catholic seminaries and, thus, infuse church teaching. Although Burgos focuses mainly on personalism’s development in Europe, he also gives brief mention of parallel movements in Britain and America, which actually predated the one that took place on the continent. In America, personalism is most closely associated with Borden Parker-Bowne of Boston University. Though his name is probably unfamiliar, he was highly influential to one PhD student whose name you will recognize – Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. But here is where things got really interesting for us: The development of personalism in Britain began when Samuel Taylor Coleridge, one of Charlotte Mason’s strongest influences, traveled to Germany and brought back the ideas of Immanuel Kant. This sparked a movement that would help shape the world in which Mason lived – British Idealism.

"Essentially, personalism says that any action, organization, theory, economic system, religion, or government is good inasmuch as it honors the inborn dignity of every person and is bad inasmuch as it does not."

In his book, British Idealism: A History, W. J. Mander traces the development of this movement, which flourished from the 1860s through the 1930s. The primary figure credited with popularizing the idealisms of Plato, Kant, and Hegel, was a professor at Balliol College named T. H. Green. Mason never mentions Green in her volumes, but his influence is present.* This is likely because one of his most ardent students, T. G. Rooper, joined the very first executive committee of the Parents Education Union in Bradford in 1890 and continued to work closely with Mason, giving lectures at local PNEU branches and assessing House of Education students, until his untimely death in 1903. Mason wrote about what she owed to him in the last chapter of Formation of Character.

British Idealism and Personalist Headwaters

British Idealism was very successful in pushing back against the materialism, empiricism, determinism, utilitarianism, dualism, and all the other “-isms” we associate with the age of science that followed the Enlightenment. In particular, it rescued metaphysics and religion from total cultural obsolescence. Mason would have been very pleased by this and attracted to the renewed importance given to ideas, but she was not carried away by the idealists. As often happens when one movement arises in response to another, the pendulum swung too far in the opposite direction. Many of her contemporaries slid all the way into Absolute Idealism (or “monism”), which states that all things are one; matter is ultimately not real in itself, but, rather, a construct of the mind. It does away with dualism, to be sure, but it does so at the expense of the individual – most importantly, the individual person. Others who had also been inspired by Kant arose in opposition, and in 1902 Henry Sturt coined the phrase “personal idealism” to differentiate them from the Absolute Idealists. The name stuck, even though these thinkers probably should not have been called “idealists” at all. They acknowledged not only the real-ness of the material world, but the moral imperative to study it. As embodied persons, we are part of the material world; to flourish, we must understand and attend to our physicality. But we are not only material, and we resist being reduced to such. Most personal idealists believed in a personal God (as opposed to an impersonal energy or a disinterested or authoritarian deity) who had endowed all those who bear His image with a dignity that requires honor. Each is unique, irreplaceable, and of inestimable worth as a self-determining individual, but each is also made for relationship with other persons, with God, and with the non-personal world. Here, we have made it to the headwaters of personalism in Britain. And who do we find waiting for us there, but Charlotte Mason.

Ongoing Research

Finding out that early personalist thought could be found in Britain led us to an exciting resource: The British Personalist Forum, an organization founded by R. T. Allen dedicated to preserving the legacy of personalist thought in Britain and promoting the continuance of personalist ideas worldwide. Lisa and I had dinner with Professor Allen and one of his fellow board members, Dr. David Jewson, while we were in residence. They had never heard of Charlotte Mason, but it only took moments for them to see the striking parallels. When the evening concluded, we gifted them with Mason’s sixth volume and two monographs, and they invited us to introduce Charlotte Mason as an early personalist thinker to their audience.

And so, Lisa and I continue to meet weekly. There is so much work left to do. Currently, we are rereading the volumes and coding them for personalist themes, as well as noting where she might diverge from common personalist thought. As we read, we are gleaning fresh insights and nuance that we simply could not see before. In some ways, it is like reading her words again for the first time. We look forward to sharing the fruits of our residency with the Mason community soon, and we are very grateful to the University of Cumbria and the Charlotte Mason Institute for making our research possible.

* For example, we believe that Mason’s “science of relations” is rooted in Green’s educational ideas, though she takes them further to create what she considered to be her only truly original contribution.

Bio

Jen Spencer, EdD, first encountered Charlotte Mason in 2001 and has been a student of hers ever since. After beginning her career as an early childhood public school teacher, Jen moved into the homeschool sector and then into private schools, establishing Willow Tree Community School in 2011. She has had several excursions to Ambleside for research and to help digitize the Mason archives at The Armitt Museum and Gallery. In 2016 she was hired by the Charlotte Mason Institute (CMI) to create Alveary, a comprehensive curriculum for schools and homeschools that continues to be published yearly. In addition to helping out with her two new grandchildren, Jen currently enjoys working with CMI to create continuing education courses for teachers who wish to become certified in Mason’s methods. She was appointed by the University of Cumbria and CMI as a Visiting Research Fellow in Charlotte Mason Studies from 2020-2025 and as a scholar-in-residence in 2025.